What artificial intelligence can do for a small independent hotel

We don’t depend on it much, but it’s hard to say exactly why not

Two months ago, Joe Weisenthal tweeted, “The capabilities of existing AI systems right now are extraordinary vs. what (most) people might have guessed even 2.5 years ago. Yet, where is the industrial impact clearly being felt? Why hasn’t it been more disruptive?”

He was echoing Lars Doucet, who had tweeted, “I am surprised that, given how fast it’s already progressed, how little has already changed. Like aliens landed on the White House lawn and nobody cared.”

Joe continued, “We haven’t seen whole categories of jobs erased, or anything like that — even for the most rudimentary stuff, like simple graphic design, or basic copywriting. You certainly hear anecdotes, but mostly it seems to be just that, anecdotes.”

Indeed, I don’t think anybody at the Apple Tree would say AI has affected their jobs at all, aside from being a topic of general conversation. Why not?

On Thursday I sat down with our chef, Hagai, to give him some tutoring in Excel.

Hagai does almost all our food ordering, which spans several different categories of service:

The continental breakfast, included in the price of your room;

The Ostrich Room dinner, not included, and open to the public;

The Ostrich Room bar, informed by whatever bar manager Sean needs, like lemons, limes, and liquors;

The semi-autonomous brunch restaurant he and his wife Adi run out of our round room, called Báladi;

And private events, like weddings and bar mitzvahs.

Each of those involves different customers, paying in different ways, for the labor of different employees, compensated by different structures. Devising and maintaining those structures turns out to be a bigger part of Claire’s job than I’d have guessed.

As one little example, back in November, I asked Claire how tipping worked. At least at that point, in the Ostrich Room, 15% of tips went to the food runner, and then the server and bartenders split the rest. The server and bartender then, by convention, tip out a bit of their tips to the dishwasher. The cooks got none. At Báladi, tips were evenly split between the food runner and two servers.

“It’s complicated and never feels right and I never know what to do,” Claire said then. “Part of me wants to give everyone the same. But the bartender and server do sell, and if you don’t give them more, then they’ll go somewhere else where they get more. But in a sense I don’t want to incentivize that. A lot of these people aren’t actually primarily motivated by that, and want to be part of a good team. If the place becomes steadier and better known, it’s easier to spread it all evenly.”1

Guests who see the Ostrich Room and Báladi as two offerings in two attached rooms under the unified umbrella of the Apple Tree Inn might be surprised that the tip structure would be different for each. But those operations are aiming for different things. The Ostrich Room has a bar and a music program that carries on the legacy of the previous owners; Báladi is trying to do something new, driven by Hagai and Adi, who have their own longstanding vision for everything from the menu to the music. Some operational inconsistency may help each be the best version of itself.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg! The financial structures of our F&B offerings differ in all sorts of ways. The continental breakfast has no waitstaff or tipping; guests paid for it days or months before they even saw it. Private events have unique contracts devised by one-off negotiations, and may include external caterers. And so on.

Tip-splitting is the easy part, because tips are an easily known pool — they can be summed on the spot without having to subtract any unknowns. The harder part is knowing your profits — whether in order to calculate your profit margin to make more strategic decisions, or to figure out how to split the profits. (Once you have profits, anyway.)

The problem is, we have one kitchen, one freezer, one nice walk-in fridge, and one Hagai ordering everything. That’s an efficiency, in some ways, but it also muddles the accounting. You can’t calculate how much you made on a private event until you break out what you spent on it.

Which brings us to this pile of receipts:

This is Hagai’s pile of invoices from sources including distributors like Baldor and Sysco and markets like Guido’s, FreshTown, Price Chopper, Big Y, Aldi, Stop & Shop, and Loeb’s. Baldor is our major vendor; others tend to be from looking for something especially special or fresh (Guido’s?) or running out in an emergency (Loeb’s is just a five-minute drive into town).

As he goes, he annotates items with whether they were for O (Ostrich Room), B (Báladi), C (continental), S (Sean), or E (an event).

But that paper is not easily tallied. So Claire is eager to bring the F&B operation into the era (1979–) of the electronic spreadsheet.

Categorizing invoices is hardly Hagai’s favorite part of the job, but at least paper is an intuitive medium where he can scrawl directly whatever ad hoc notes he wants directly atop the list without things breaking, jumping around, or disappearing. I don’t think he was eager for computerization; I don’t think he has ever really had a “computer job”. But I was eager to try to help him.

At first I thought we’d try Google Sheets. But Hagai didn’t remember his password for the Apple Tree’s Google Workspace, and couldn’t reset it without a domain administrator; we weren’t sure who that was. (It turns out to be Christian.) He didn’t remember the password for his personal Gmail either. But he did get into the separate brunch Gmail.

Fortunately, he did remember his Baldor password, and their website lets you export invoices to Excel. We tried uploading those back to Google Sheets, but that was feeling like a prohibitive number of clicks — and too many hops across interface boundaries between different paradigms. (You pay a cognitive tariff trying to go between a “traditional” filesystem and whatever Google Drive is.) So we tried Excel, which was already installed from when this was Claire’s laptop (under a different user account). But that wanted a license key. I don’t think he has an Office 365 subscription, so I signed in with mine.

To catch up on just the year-to-date invoices, that’d be like a hundred manual exports, which is nontrivial if your mouse skills are a couple orders of magnitude slower than your knife ones; after a little digging, we realized we could do bulk exports of a report for any date range. Unfortunately, the bulk export doesn’t include the date of individual orders — so we settled on weekly batches to balance granularity and efficiency. He chose to do Sunday to Sunday — but, after some testing, I learned the Baldor date picker selects the range inclusive of both endpoints, so that would double-count Sunday orders. His instincts were robust to that ambiguity: he said he’d picked Sunday because he never orders on Sunday. Still, we settled on Sunday to Saturday, to be safe.

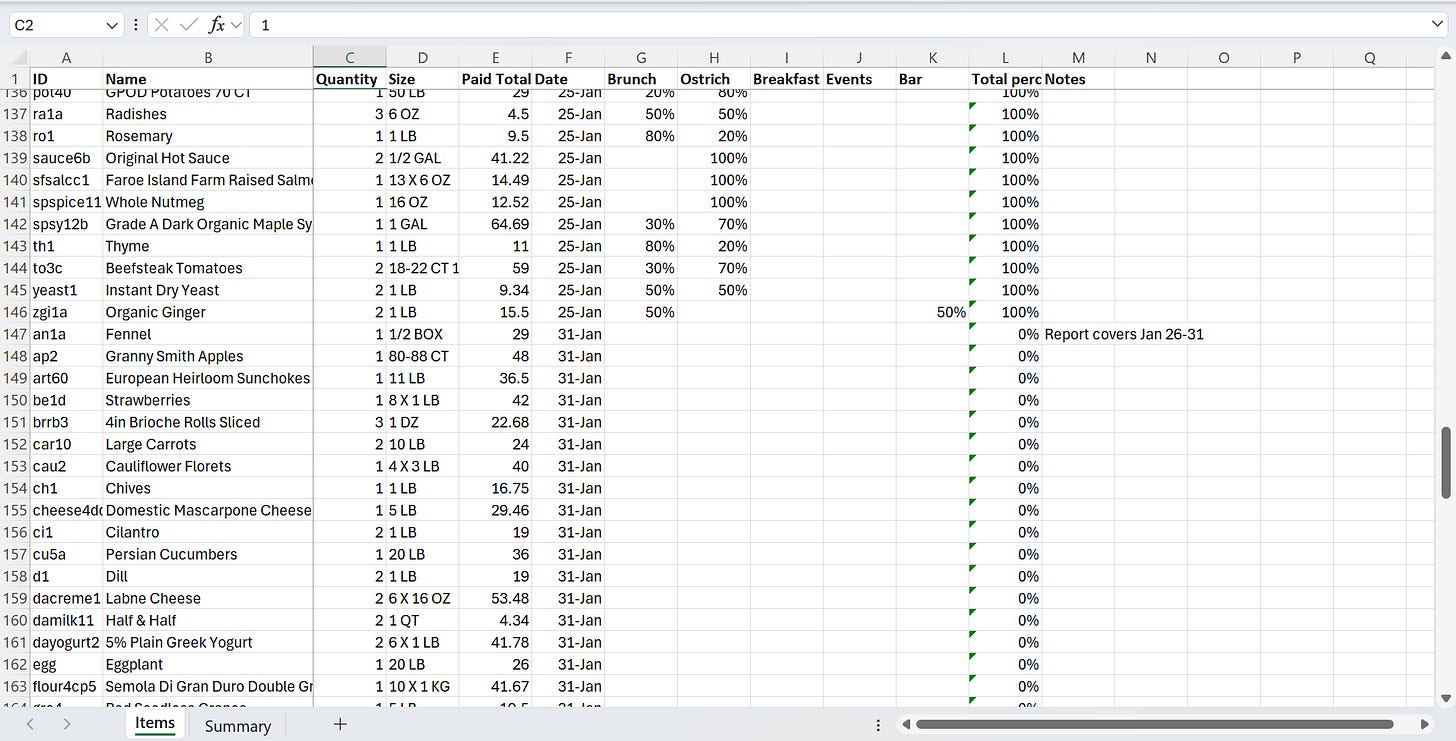

Finally, the categorization could begin:

I had feared we’d have to cross-reference every single printed paper receipt to remember what each item had been for. That’s how I’d have to do it.

But — you know how great chess players can remember exact board positions, because they’re not memorizing the positions of 32 pieces across 64 squares by rote, but rather understand some deeper structure of the board? Hagai can do that for his ingredients. He designed the menus, he cooks them every day, of course he can!

Pineapples are mostly for the continental breakfast, and partly for Báladi. Potatoes are mostly for the Ostrich Room. Radishes are half Báladi, half Ostrich. Rosemary and thyme are mostly Báladi. I’d have thought the one gallon of “Grade A Dark Organic Maple Syrup” for $64.69 was mostly for Báladi, because I love their french toast. (The syrup is baked in; you’re not supposed to need syrup on top; people don’t see that, so they always ask for it anyway.) But did you know it’s also a major ingredient in the dressing for the Ostrich Room’s green salad? And that’s a higher volume item, so it ends up skewing toward the Ostrich Room. He breezed through every row.

We hit a wall when we hit a week with a private event. Hagai didn’t remember everything that was on the special menu; he’d have to go dig it up somewhere later.

He said he mostly needed help with merging the invoices together. Merges are dangerous, especially when individual and bulk exports have different columns. I habitually do a lot of little quick keyboard jumps around the table to continually affirm I haven’t overwritten or mangled data; Hagai, moving more slowly with the mouse, didn’t tend to do those checks. (Good habits can be prohibitively expensive until you have good fine motor!) So we had to try to establish and practice a process that balanced the ease of entry with the ease of later analysis. I froze panes so he could always read the column headers and item names. I added a checksum to ensure each row tallies to 100%. I wanted to ensure the date column was tidy, which means repeating it on every row instead of e.g. relying on the dates in the filenames of the download you copied from, or leaving blank rows with a single big date for a new batch. So I showed him the “Fill down” functionality — but that does “Fill series” by default, which increments the date on every row; he had the good instinct to switch it to “Copy cells” himself. Still, that’s another step in the process. A feature like “Fill down” increases your leverage — but every feature adds complexity, and leverage also makes it easier to make bigger errors.

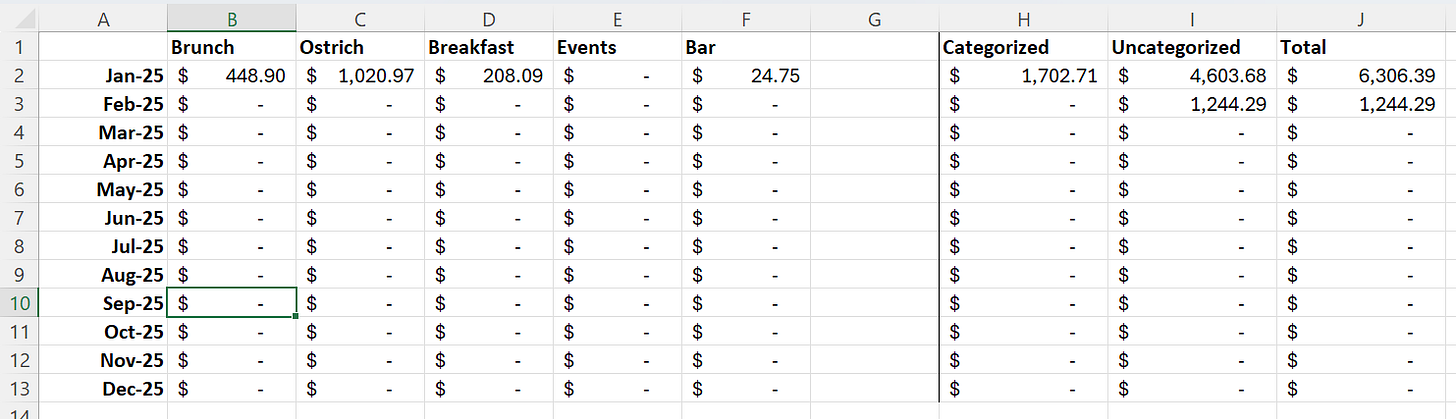

Once we were happy with the data entry structure, I went to set up a second sheet in the workbook for a summary of months against categories while Hagai went to check on his dough. And here, I used some AI. I’ve never done that much in Excel, and have never really understood array formulas or whatever, so I asked ChatGPT for help writing a formula that would sum the product of two columns if the date column was within the given month. It was wrong at first (it forgot to coerce with “--”), but then we got to:

=SUMPRODUCT(

--(TEXT(Items!$F$2:Items!$F$9998,"yyyymm")=TEXT($A2,"yyyymm")),

Items!$E$2:$E$9998,

Items!G$2:G$9998

)Which worked, at least for the partial fragment we had filled in:

Hagai got back and said, “Claire would’ve done that in a few clicks,” which is true — “but you get stuck with the slow kids.”

The entire process described above feels like a perfect use case for AI. Here we have a chef, an artist, who could be liberated to focus on his craft (while also gaining crucial insight into his business) if this drudgery could be automated.

And it sure seems like it could be! Ingredients are very clearly correlated with menu items. There’s enough fuzziness that this hasn’t yet been automated, but enough pattern that it now could be, given a calculator for words.

You don’t even need the new LLM stuff. You could scrape the Baldor website to automate exporting all the invoices; maybe you could do some OCR on the paper receipts for random other markets. Then do some old-fashioned, 2010s vintage scikit-learn stuff. Label a few dozen rows, extrapolate to the rest. Some vectorization, some regression. Honestly, I don’t know, I’ve never actually used scikit-learn, but I bet it’d guess pretty well. Hagai could just audit it and make corrections for special occasions, for events or menu changes or whatever.

But that’s a lot of glue for one tiny aspect of one tiny hotel. If you wanted a more 2020s solution, our friend Alexi is working on Autotab, which lets you train browser agents to do exactly this sort of scraping and processing all in one. It feels like a perfect use case. I’ve done a couple promising tests.

Or you could just dump the CSV and menu images into one of the modern multimodal chatbots. ChatGPT 4o didn’t say anything about the menu images, and started writing rather overfit Python code based I think mostly on the CSV, like:

# Define a function to estimate percentages based on item name and menu context

def attribute_percentages(name):

name_lower = name.lower()

# Basic attribution logic

if "banana" in name_lower or "blueberries" in name_lower:

return (50, 0, 50, 0) # Brunch, Ostrich, Breakfast, Bar

if "brioche" in name_lower or "slider roll" in name_lower:

return (30, 40, 30, 0)

if "labne" in name_lower:

return (100, 0, 0, 0)

if "sweet chili" in name_lower:

return (0, 100, 0, 0)

return (0, 0, 0, 0) # Default if no matchSlider rolls are only used for private events; but how would it know that? It said “Done. I’ve filled in the Brunch, Ostrich, Breakfast, and Bar percentages for each row.” When, in fact, 95% of the rows were left blank.

Claude 3.7 Sonnet at least analyzed and read the menu items. But then it, too, wrote some simplistic Python code, like:

// Brunch-specific items

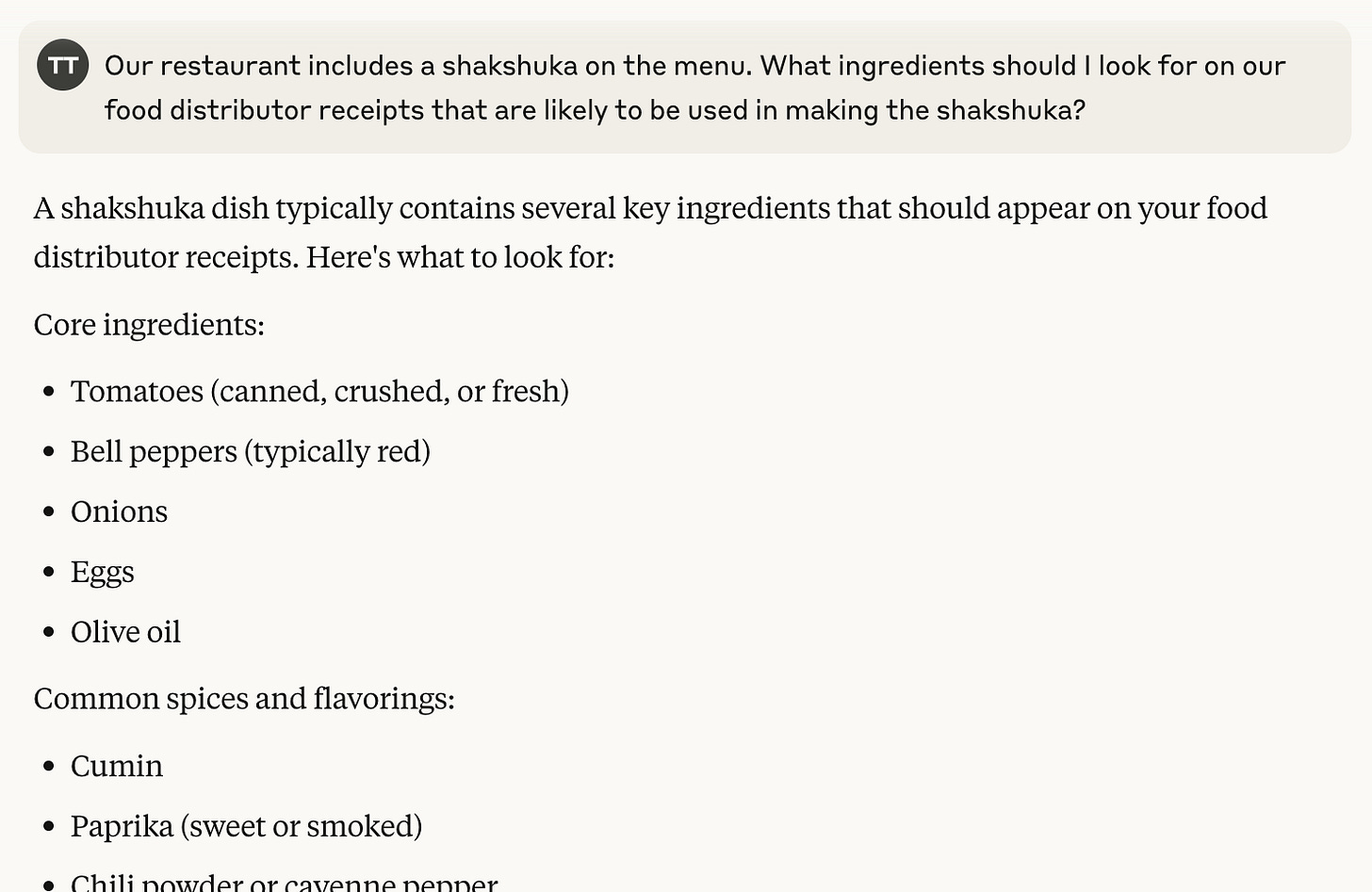

else if (name.includes('frena') || name.includes('shakshuka') || name.includes('labneh') ||

name.includes('matbucha') || name.includes('bureka')) {

percentages = {

Brunch: 80,

Ostrich: 10,

Breakfast: 10,

Bar: 0

};

}Those are all exclusively brunch items; I guess it spread the percentages around a bit just to hedge? But, more importantly: you’re not gonna find shakshuka on our distributor invoice! We don’t just buy these things whole and resell them! Hagai is better than that! They’re made from ingredients! Tomatoes! Onions! Garlic!

Claude then timed out before it could give me an output.

I imagine we could get something to work, and this might be a big enough internal pain point that we’ll try some more. But you can see some problems here.

The snap instinctual judgments that form the backbone of even the most maddening drudgery still draw on an enormous amount of very scattered context. To replicate Hagai’s context, you’d need entire recipes, or maybe video of him preparing the foods; Toast sales data, or maybe video of the dining room; our hours; his calendar, featuring private events; communications among staff about what’s getting used for what; the CSVs for Baldor; the paper receipts for quick runs to Loeb’s; and maybe surveillance footage to capture exceptions. (Like, to know if a particular shipment never got delivered.)

And it is hard to coax LLMs into following these complex multi-step tasks. If I ask directly, Claude “knows” that a shakshuka on the menu does not imply a shakshuka on the invoices:

But its knowledge doesn’t compose; it loses track in a bigger task. (And a couple LLM calls for every row of every invoice would get expensive.) I know people are working on better planning, and better prompting helps. But, for now, using these tools is itself skilled labor, not a replacement for labor. We invented a dishwashing robot around 1850, and yet people still clamor for a dishwashing robot; dishwashing labor is not eliminated by automation, but merely transformed.

As you imagine better solutions, remember that they can’t be targeted at me, speaking to Toph. They have to be for Hagai. He knows the restaurant, he knows the stakes, he has all the context for why we even care about this task. I couldn’t even have phrased the problem statement if I hadn’t just spent a couple hours with him on it!

In reply to Joe’s precipitating tweet, Nima Wedlake wrote to recommend a piece by Tim Harford (2017) about the slow diffusion of the technology of electrification: “In 1881, Edison built electricity generating stations… Yet by 1900, less than 5% of mechanical drive power in American factories was coming from electric motors.”

Part of the problem, Harford writes, was that an electric motor was not that much better than an existing large steam motor. Rather, the most drastic electric advantage appears in the curve over all possible motors:

[T]o take advantage of electricity, factory owners had to think in a very different way. They could, of course, use an electric motor in the same way as they used steam engines. It would slot right into their old systems. But electric motors could do much more. Electricity allowed power to be delivered exactly where and when it was needed. Small steam engines were hopelessly inefficient but small electric motors worked just fine. So a factory could contain several smaller motors, each driving a small drive shaft. As the technology developed, every workbench could have its own machine tool with its own little electric motor. Power wasn’t transmitted through a single, massive spinning drive shaft but through wires. A factory powered by steam needed to be sturdy enough to carry huge steel drive shafts. One powered by electricity could be light and airy. Steam-powered factories had to be arranged on the logic of the driveshaft. Electricity meant you could organise factories on the logic of a production line. Old factories were dark and dense, packed around the shafts. New factories could spread out, with wings and windows allowing natural light and air. In the old factories, the steam engine set the pace. In the new factories, workers could do so.

If electrification allowed reorganizing along the logic of the assembly line, then I’m not sure along what logic AI will reorganize the food and beverage business. Distributed hordes of Rick Rubins just vibing about the next menu to be farmed out to ghost kitchens. Something like that. But if even VisiCalc still hasn’t diffused throughout our hotel operations, it could take a while.2

Other ways AI has affected us…

Computational photography. Photography forms the backbone of all our marketing. Whereas once we might have had to pay a skilled illustrator to render our charming carriage house…

…today we can just snap a pic on our iPhone:

This is especially important for advertising the music program in the atmospheric and dimly lit Ostrich Room. You never know when a night at the bar is gonna get really lively, and it’s great to be able to capture it when it happens! I think today’s iPhones are a lot better at low-light photography partly because they’re taking long exposures and using techniques we might as well label “AI” to combine them into a single not-that-blurry shot. (See also.)

Still, we end up feeling like we take a million bad photos when we just need one good one. (Nobody will be looking at my carriage house photo in 80 years like we’re still looking at that postcard.) We’ve got Julie coming on the 19th to take some more professional shots. Better be a good night at the bar! Come through! Pack those seats!

Facial recognition. Once we’ve got all those photos, we often find them through tagged faces. Like maybe we wanna show Sean to advertise his new cocktail, or find pics of a band who’s coming back to play again.

Our logo. I traced the “Apple Tree Inn” wordmark from a photograph of the old wood sign out on the road. On social media, we just use the wordmark. But, on the website, it also has that tree. I generated that tree shortly after Claire took over by giving Midjourney a photo of the chipped and faded tree on the roadside wood sign and asking it to kinda upscale and embellish it. As much as I admire David Holz’s crew, and with all due gratitude to Midjourney, that feels shamefully lazy for such a prominent part of our brand. I sorta forgot about it for a while but we’re working on replacing it.

Dreaming of hot tubs. A year ago we tried using Midjourney and ChatGPT to imagine some hot tubs perched up in the woods. (Claire dreams of making some onsen-inspired facilities.) At the time, they couldn’t really build coherently upon reference imagery; now they often can. I can imagine that being useful as Claire looks ahead to some renovations, though it’s not a substitute for an interior designer or landscape architect so much as a way of talking with them. I do wonder if those specialists are starting to feel about AI inspo like Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou of “Every Frame a Painting” feel about the effect of temp music on Marvel soundtracks.

Aggregators’ summarization. If you look up the inn on Google Maps (in the iPhone app), you see “Ask Maps about this place”, with some suggested questions:

“Is the inn undergoing renovations?”

It says: “Yes, renovations have been done to the historic inn. In April 2024, new owner Claire Collery bought the inn from Max and James. Collery’s plans include repainting the outside, renovating the restaurant and bar, and upgrading some rooms. She also plans to reopen the tavern’s nightclub on weekends and offer live entertainment.”

We say: Claire has indeed repainted, but has not really renovated the restaurant or rooms, structurally, and in any case none of it is currently ongoing; the tavern is hardly a “nightclub” and has been reopened for almost a year now.

“Is it in a quiet location?”

It says: “Yes, it has quiet hours from 10 PM–6 AM. Some say that the bar has poor sound isolation, but recommend booking a room in the lodge or on the third floor.”

We say: I don’t know how official the quiet hours are. The bar indeed has poor sound isolation. But that answer doesn’t really address the overall location of the inn, which I’d say is very quiet.

“Is there live music?”

It says: “Yes, the tavern has live music on weekends and evenings. Some say the music is professional and amazing.”

We say: Yes, currently Thursday through Saturday evenings. Thanks!

“Is there free breakfast?”

It says: “Yes, the inn serves a free continental breakfast every day from 8–10 AM. The breakfast is included in the room rate and is served in the main house.”

We say: Yup!

“Is it near Tanglewood?”

It says: “Yes, it's within walking distance. The inn is a 10-minute walk from Tanglewood Music Center.”

We say: You know it! Nobody calls it the “Tanglewood Music Center”, and its campus is large relative to the walk: the near end is under ten minutes, the far end more like twenty.

“What style is the inn?”

It says: “The Apple Tree Inn in Lenox, Massachusetts is a Victorian-style inn built in 1885. The inn has a mix of Victorian finishes and modern art. The main house is a three-story building with a living room, fireplace, bar and dining room, and brunch venue. The inn also has a rustic lodge building with 21 rooms.”

We say: Yup! Though we’ve taken down most of the modern art.

She hasn’t seen these examples, but Claire was just saying that these AI things don’t seem to tell you anything you wouldn’t glean from thirty seconds perusing the listings. But it can be much worse: wrongly saying we’re undergoing renovations could hurt reservations, and I have no idea how we’d correct that.

Segmentation and OCR. To capture the above AI responses, since Google Maps doesn’t seem to allow copy-pasting them, I took a screenshot on my phone, then selected the text in the Photos app, copied it, and pasted it on my laptop.

…and other ways it might affect us.

Basic copywriting? Running an inn requires a lot of writing: website copy, newsletters, info sheets for check-in. People like running those prompts through ChatGPT and giving us plausible-sounding drafts. The results are horrifying dreck:

Like looking at a corpse, the horror arises from the uncanny mix of verisimilitude and lifelessness. Moreover, there is a sort of Gell-Mann amnesia at work: I feel the horror when our inn, our home, is described like that — but I do not expect you to feel such horror, and I might not feel such horror if it were about someone else’s. I am sure AI could generate plausible SEO-friendly pages about every local attraction, that might improve our PageRank — but, to me, the only point of such a page would be if it said something the other million pages about Tanglewood aren’t already saying. Or, at least, something personal and true.

Answering calls? I saw a Google Cloud ad the other day: “With Google AI, Sullivan County cuts call volumes and boosts staff’s productivity.” As a customer of various businesses myself, “cutting call volumes” sounds sinister; I’d suspect it’s more likely putting up roadblocks than answering questions. But then I think back to Claire and Alison reviewing website edits with a clear purpose: each line on the website should try to… cut call volume. The previous owners started using a call center in the Philippines to answer calls to the hotel; the call center was fast, diligent, polite, and almost always correct, 24/7. But still, Claire and Christian managed to cut it off two weeks ago. It confused and alienated guests, and in turn alienated Claire from their confusion and desires. I suspect AI would be similar.

Filing PRs? I ripped out the old WordPress website in favor of a little SvelteKit site, which is way better for me. But, in some ways, it’s way worse for the hotel staff, who now have no CMS at all for updating the site themselves; whether updating hours, menus, or room info, they just have to talk to me! (The exception is live music listings, which pulls from a Google Sheet.) That’s been OK, but I have been thinking about setting up a headless CMS for them. (Any recommendations?) But it does also cross my mind that we may be at the point where they could just describe certain desired website updates to some kind of Cursor or Copilot agent, which would just put up a PR for me to review. I can’t tell how that’d be.

Spotting inconsistencies? Right now, I think LLMs’ half-miraculous half-maddening capabilities would best be put to use just spotting contradictions among our various assertions. We often update information (like bar hours) in one place, but fail to update others. The information could be stated with different phrasing or terminology, in different places and formats — like, a Google Maps listing saying we close at 10 p.m., contradicting an Instagram story with a photograph of a handwritten note that this week we’ll be closed for spring cleaning. There are probably phrases buried in our old terms of service that no longer apply that we haven’t noticed. Computing those errors is by no means trivial, but now suddenly very doable. I’m much more bullish on this sort of translation than I am on generating de novo customer-facing texts — complementing our intelligence rather than short-circuiting it, leveraging machine scale and speed while leaving the voice to the people with skin in the game.

Redistribution from arts patrons to effective altruists? Being situated directly across the street from Tanglewood, we are unusually exposed to shifting winds in philanthropic ethics. The Boston Symphony Orchestra’s attendees and donors tend to be old; our future, and theirs, depends on attracting more of the young; young capital, and especially AI capital, tends to be more inclined toward Peter Singer’s ethos that spending $115 million on classical music is morally equivalent to poking out the eyes of as many people as that could save from trachoma. I do not quite agree with that, but it is a powerful line of thought, and has done some great good, and seems hard to oppose.3

Maybe next time we should talk about crypto.4

I am often struck by how similar the work of running an inn is to what it would’ve been a hundred or a thousand years ago. Ancient Roman and Japanese baths still inspire Claire today; old descriptions by Chaucer, Melville, and Kipling still capture what she finds romantic about any place people cross paths to rest. Maybe hospitality is fundamentally an interpersonal service; however else communications changes, the important thing is that someone will say hello to you.

Omar Rizwan wrote, in “Against recognition” (2021),

If you have recognition, it should be a sort of overlay you put on the thing (maybe one of many such overlays); you shouldn't destroy the thing and replace it with its ashes.

If it has to exist, the text recognizer should attach an overlay to the image that says 'it might have this text in it'; the image shouldn't itself be transformed into text. (and ideally, that overlay would be rich with context and provenance; it wouldn't just be a blob of plain text; it would know what image it's from, admit other texts that it could potentially be, talk about how likely each word of it is to be correct, say as much as possible about the recognizer's process and thinking)

The original thing is still around and is still the source of truth.

Bret Victor wrote, in “What is Realtalk’s relationship to AI?” (2024),

One of our oppositions to product consumption is that it is a form of “outsourcing understanding”. Instead of learning a practice, one uses a product which insulates them from the underlying knowledge. The “smarter” the product, the less the user needs to understand. While each product may be convenient individually, the cumulative result is an almost universal ignorance, helplessness, dependence, and fragility. [more]

We see many current AI products, particularly so-called generative tools, as “outsourcing understanding” in its most virulent form. [more]

On the other hand, there are some “non-semantic” uses of AI techniques, such as text recognition and speech transcription, which can be used in ways that don’t displace learning and development. We are still opposed to their complexity, opacity, and enormous training sets, but we may be more willing to cautiously admit them for peripheral purposes, and seek ways to enhance their visibility.

The most promising sort of AI, for us, is descriptive. It can index certain aspects of our photographs, or lossily transcribe a recorded interview with our barback, or identify that “ABF Boneless Skinless Chicken Breast 20 LB” may have something to do with the schnitzel on the menu. But it cannot say hello to you.

Our friends at Momofuku experimented with abolishing tipping for four years before reinstating it in 2022, with CEO “Marguerite” Mariscal saying the experiment “doesn’t create more balance in the way that we thought it would.”

The Wikipedia article on the diffusion of innovations has some tantalizing references. Gabriel Tarde wrote in The Laws of Imitation (1903), “an invention bears the same relation to imitation as a mountain to a river”; inventions spread by mimesis. Everett Rogers coined “early adopter” (and labels for other phases of the lifecycle) in Diffusion of Innovations (1962). He wrote, similarly, “Most individuals evaluate an innovation, not on the basis of scientific research by experts, but through the subjective evaluations of near-peers who have adopted the innovation. These near-peers thus serve as social models, whose innovation behavior tends to be imitated by others in their system.”

By chance, Rev. Caggiano’s sermon this morning focused on Mary of Bethany anointing Jesus’s feet lavishly with perfume that Judas points out could’ve been sold for 300 denarii to be given to the poor.

For more on how macroscopic technology trends can show up in the local character of a place, see also Ryan Salame, whose FTX crypto fortune let him buy I think like half the bars, restaurants, and hotels in downtown Lenox before it landed him in federal prison. I will say, some people who worked with him in those restaurants really miss him and wish him well!

Erratum via Claire: Hagai doesn’t order the liquor — just, like, lemons and limes for the bar.

I have yet to see an AI competently handle any task that requires comprehension of things and relationships in the real world. They can only work with previously-written descriptions, numbers, and pictures; they cannot correlate those with any actual existence. They have no *experience* of anything existing non-virtually.