Econ 101: Profit margins

You have to make a lot more than a dollar to justify spending a dollar

Continuing our series from last week on basic economic ideas viewed through the lens of the hotel.

People have a lot of ideas for Claire. Like: research shows that people weigh their first impressions highly; a little touch that goes “above and beyond” at check-in can go a long way; what if, instead of K-Cups, you had unusually nice espressos for people when they arrive? They can relax by the fire as you take their bags to the room. Imagine how cozy that would be!

That’s not a straw man; I remember Claire dreaming about the coffee opportunity before taking over. But if you catch Claire on the lobby floor in operational mode, you might meet resistance. You suggest something that costs $1,000, she immediately replies: “OK, but at a 10% profit margin, that means I have to sell $10,000 worth of rooms; that’s almost a hundred room-nights; that’s like two extra rooms every weekend. Do you think it’d really make that big a difference?”

That math that inflates $1,000 to $10,000 struck me. I took a few Econ classes, I shouldn’t be surprised — but I have no instinct for that. If I see a $1 price tag, I think it costs $1, so I just have to make $1 to buy it. But she is able to think (on the fly, instinctually) on the margin.

I gotta think it through more slowly.

Suppose that, to have one guest for one night, you spend $90 (on front desk staff, cleaning and laundry service, supplies and prep for breakfast, heating, etc.) and then sell it for $100. You make $10, for a profit margin of $10 ÷ $100 = 10%.

Now suppose that, to have two guests for one night, you just double all that: spend $180, make $200, same 10% profit margin. Or one guest for two nights: spend $180, make $200, same 10% profit margin. Keep it simple.

Now suppose you spend $1,000 on Wirecutter’s recommended best beginner espresso machine. People love coffee! One in three will partake; of those, one in ten might mention it to a friend; of those, one in a hundred might actually book a room.

When they come, we spend $90, they spend $100, and we make $10. We’re just 1% of the way toward paying off the coffee machine.

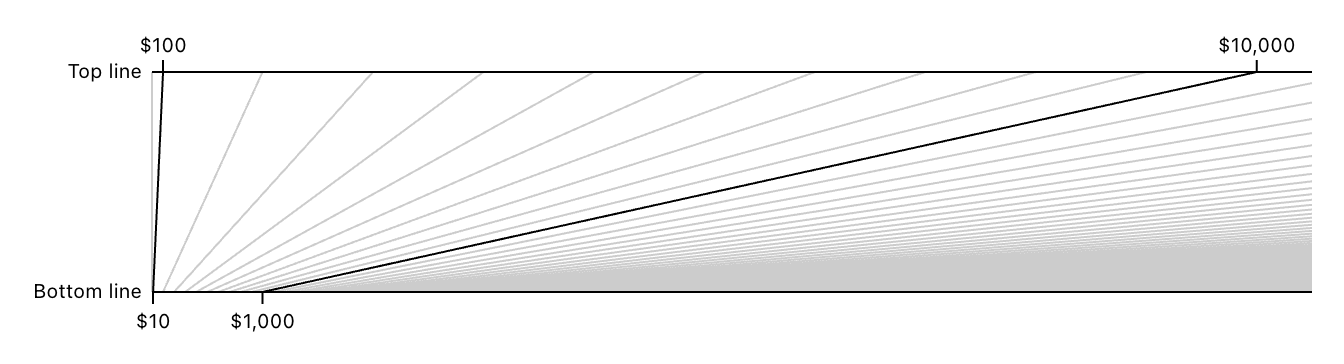

You can think about this in terms of the literal “top line” and “bottom line” of the income statement. When you take in $100 at the top line, $10 flows down to the bottom line. So if you spend $1,000 out of the bottom line, you need to take in $10,000 more at the top line.

The espresso machine also comes with the ongoing costs of coffee beans and the labor to step away from the desk, make the espresso, go out and buy more beans, fix the machine occasionally, and so on. So, in our example, it probably erodes the 10% profit margin, too. And the lower your margins, the more expensive the espresso machine becomes:

That is, the top-line revenue needed to cover bottom-line expense of $1,000 grows toward infinity as your margins fall to zero.

And then, if your margins fall below zero — that is, if you’re losing money, like we are — then what? At that point I think you just can’t think this way. If your margins are −10%, then I guess dividing $1,000 by −10% makes −$10,000. Maybe you could interpret that to mean you’d need take in $10,000 less revenue at the top line to recoup the cost, i.e., you should wind down operations.

If you never think about profit margins, you go broke; if you only think about profit margins, you go crazy. It’s a good tool and a terrible master.

Above, I assumed that the revenue and expenses of two room-nights were exactly twice those of one room-night. Of course that’s nowhere close to true, thanks to things like economies of scale. It’s generally much less than twice as expensive to have two guests than it is to have one. Many costs don’t scale with the number of guests at all. We still only have to buy a hotel truck once.

Investment in that sort of fixed assets of the business is called “capital expenditures.” (Or something like that; this is certainly not financial advice.) The calculation above did not include the cost of the truck, or of repainting the hotel, or of buying the office computer. Instead, profit margin is just based on “operating expenses” — the ongoing and variable expenses, like buying the bagels for the included continental breakfast, or paying Karla to make the beds.

But what counts as which kind of expense is kind of a matter of perspective. Like, if you’re FedEx, the cost of trucks is probably an operating expense. We want to be able to consider the impact of, say, the bar and the music and the brunch separately — but for now they’re all intertwined. It’s very hard to tease out any real number for the actual literal profit margin of any part of the business. Are these continental breakfast eggs (a cost of providing the room), brunch eggs (a cost of Báladi), or dinner eggs (a cost of the Ostrich Room)? Rooms generally have bigger margins than the restaurant, but you could say you need the restaurant to attract anyone to the rooms.

Only very rarely can you isolate some calculable margins. For example, Sean cares a lot about his cocktails, and has been buying more expensive scotches, which I guess you can sell at a higher percentage markup with a Veblenesque demand curve.

In these early days, Claire is kind of personally thinking of almost everything as a capital expenditure. It’s all start-up costs, the price of just figuring out the business. There’s that part of her mind that can’t help but consider the profit margin — but it’s just one factor calibrating the degree to which she focuses on different things. It’s almost more like a thought experiment, an intuition pump, a tool for thinking through the corners of a very high-dimensional space. A hotel manager needs to think about profit margin, but she’s ultimately thinking more like the owner, who cares more about yield — the return on your entire investment, capex and all.

Lately Claire’s been thinking a lot about different wallpapers with which to potentially re-do the lobby and stairwell. It would be almost impossible to attribute any marginal room booking to a change in the wallpapers. But it can signal care and attention to detail; it can make people let their guard down, trust you more, stay longer, spend more. And most things she’s thinking about feel more like that. Did switching from Lightspeed to Toast improve the restaurant margins? Maybe a little bit in throughput on busy nights, but the more important thing is that it made the employees using it happier, which you’re gonna need to do anything else. Is Claire’s hotel history exhibit going to improve margins? I mean, maybe, hopefully, in the long run, but that’s the wrong way to think about it! You gotta do stuff you’re proud of.

Ten years ago I interviewed my friend Adam to write a little bio of him for our book club, and I often think about him saying: you know, you sleep 8 hours, work 10 hours, commute 2 hours, eat 2 hours… once you subtract all that out, you might only have an hour left in the day to pursue your real passions and hobbies. It’s so little time that fluctuations in the other stuff can easily erase it entirely.

Suppose writing a weekly newsletter takes you six hours. How many weeks’ worth of marginal time does that consume?

Two weeks ago, I was working late into the night on my last installment of this newsletter, and Claire came in to check on me. She said, just think: every additional minute you spend on this one makes it less likely you’ll send one next week.

Now that’s thinking in margins!

Mailbag

John Branch replied to our last installment to say, “The part about staffing the front desk reminds me of the original William Baumol piece about why the arts get more expensive over time. The human touch at a hotel is a labor intensive art”.

I hazily remembered hearing of “Baumol cost disease” from Scott Alexander as an umbrella term for things like healthcare and education getting bafflingly more expensive. I should find some data on how hotels compare to those sectors. I think someone tweeted the other day that the modern travel experience is that flights are cheap and hotels are expensive. (See also, also.)

Anyway, Baumol’s original piece is just eight pages and worth reading:

Let us think of an economy divided into two sectors: one in which productivity is rising and another where productivity is stable. For the moment let us assume that there is only one grade of labor, that labor is free to move back and forth between sectors, and that the real wage rate rises pari passu with the aggregate rate of change of productivity, at 2 percent per annum. The implications of this simple model for costs in the two sectors are straightforward. In the rising productivity sector, output per man-hour increases more rapidly than the money wage rate and labor costs per unit must therefore decline. However, in the sector where productivity is stable, there is no offsetting improvement in output per man-hour, and so every increase in money wages is translated automatically into an equivalent increase in unit labor costs. The faster the general pace of technological advance, the greater will be the increase in the overall wage level and the greater the upward pressure on costs in those industries which do not enjoy increased productivity. Faster technological progress is no blessing for the laggards, at least as far as their costs are concerned.

Everything is valued not just by what it’s doing, but by what else it could be doing. A hotel room is valued partly by what someone else would pay for a private home or condo on that land. People say “oh surely you can find some local teens to help work this summer,” but they’re all off doing tech, finance, and consulting internships.

Guest book

John, Pat, Jill, and Mark came in for dinner Friday. I said hi to them and they all said they were enjoying the hotel newsletter. I said, “Which one?” Jill said, “Oh, mine is always signed ‘Claire’.” And John said, “And mine is reallly [holding hands out toward floor and ceiling] long.”

Gutsch came by on Saturday to do some research on what turned out to be our top-grossing night in the Ostrich Room so far, thanks to Wanda’s show. (We broke $4,000 in revenue! I have no idea how much we spent.) Sara and Tony also came and took some great video. Will’s mom stayed (not my brother Will’s mom — that’d be my mom — it’s a different Will) but I didn’t get to meet her. Emily came to visit Christian and inspire him to get back to reading more.

Changelog

National Grid cut down a couple dead trees close to the power lines on the front lawn for free. Thank you National Grid! Our gratitude was magnified yesterday when someone crashed their truck into the power line pole at the base of the driveway and knocked out our power for under an hour until National Grid promptly restored it. Doubly thank you National Grid!

The Stockbridge Bowl has thawed and we expect that Friday’s dusting of snow was probably the last of the season.

Announcements

It’s maple tapping season at Ioka Valley Farm!

Everything in the way of possibilities contained in, for instance, a hundred pounds is undoubtedly contained in that sum whether one possesses it or not; the fact that Mr. I or Mr. You possesses it adds as little to it as to a rose or to a woman. But a fool tucks it away in a stocking, the realists say, and an efficient man makes it work for him. Something is undeniably added to or taken away from even the beauty of a woman by the man who possesses her. It is reality that awakens possibilities, and nothing could be more wrong than to deny this. Nevertheless, in the sum total or on the average they will always remain the same possibilities, going on repeating themselves until someone comes along to whom something real means no more than something imagined. It is he who first gives the new possibilities their meaning and their destiny; he awakens them.

— Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities

Gutsch? I have questions!